“The mere sound of a plane makes me feel sick,” said a 38-year-old resident of Launglon, describing the growing terror felt by civilians in Myanmar’s southern Tanintharyi region.

Once relatively untouched by the junta’s brutal air campaign, Tanintharyi is now experiencing a sharp escalation in aerial attacks and heavy shelling from artillery.

Even as Myanmar grapples with the devastation of the recent earthquake, the military has continued its offensive in the region – bombing villages, firing artillery and from helicopters, displacing tens of thousands of people.

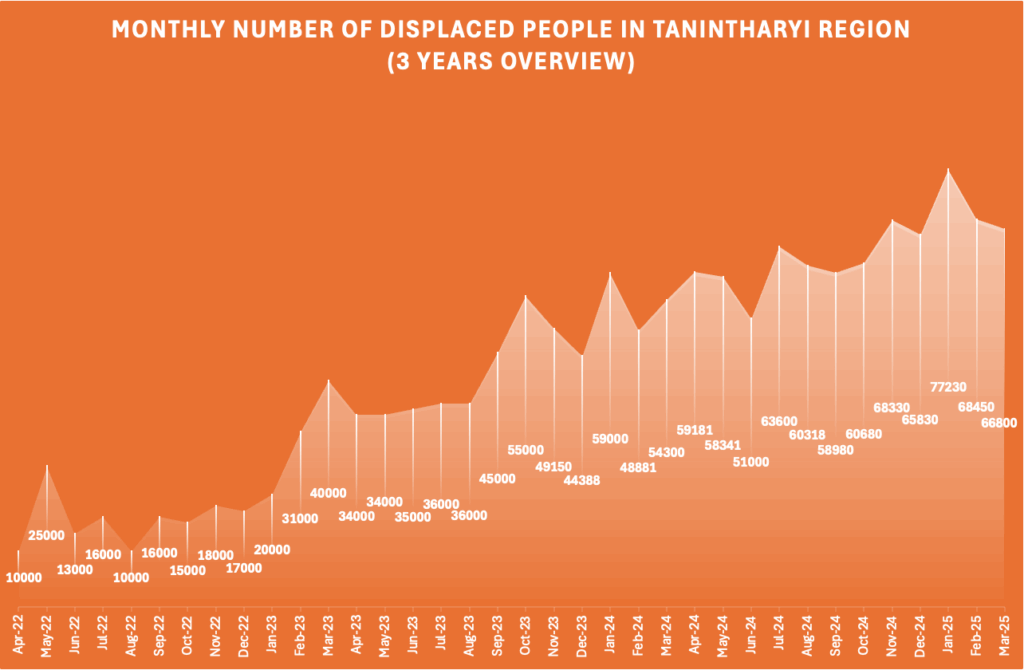

According to local data, more than 75,300 people were forced to flee their homes in April alone, as intensifying ground battles and air raids swept through the region.

Increased reliance on airpower

Facing fierce resistance and losing control on the ground across Tanintharyi, the Myanmar military has significantly escalated its reliance on airpower. This shift involves using bombings, helicopter attacks and drone strikes in an attempt to regain the upper hand against increasingly effective resistance forces.

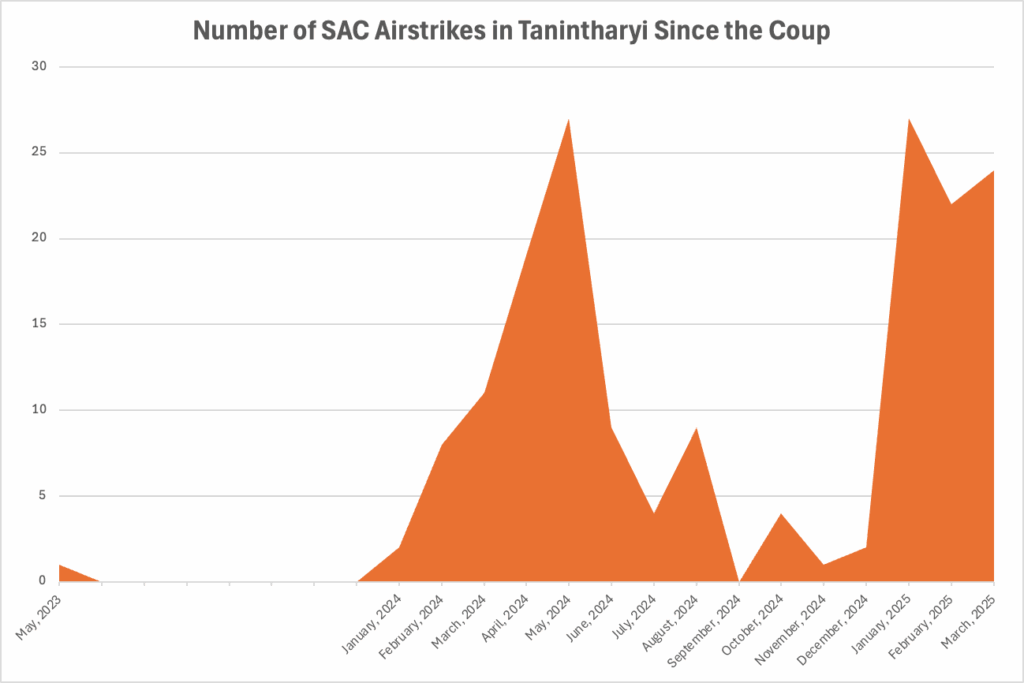

Since the 2021 coup, Tanintharyi region has endured more than 200 airstrikes, with the tempo of these attacks increasing sharply. In March 2025 alone, at least 24 airstrikes were recorded, marking a substantial rise from previous months.

This trend continued into April, with at least 35 airstrikes documented in the region.

Air operations have been intense in strategic areas such as the Maw Taung trade route along the Thai-Myanmar border, where ground offensives have faltered. Within Tanintharyi Township, residents reported at least 16 separate airstrikes in March.

The aerial bombardments have also extended beyond suspected resistance strongholds to include civilian villages in Thayetchaung, Launglon, Dawei and Bokpyin townships, often targeting communities believed to harbor anti-junta sentiments.

The junta’s increased reliance on air support became particularly evident during key battles where resistance forces have attacked and, in some cases, seized military bases and outposts within the Coastal Region Military Command area.

For instance, during the resistance’s offensive to capture the Htee Hta strategic base in eastern Dawei near the Thai border on April 12-19, the junta responded with overwhelming airpower.

Over eight days, fighter jets, transport aircraft and helicopters dropped hundreds of bombs in a desperate attempt to defend the base. The military deployed Chinese-made K8W fighter jets, Y-12 transport aircraft and Mi-17 helicopters, many of them flying from the Myeik Air Base headquarters, sometimes from Dawei airport.

Similarly, air support was heavily utilized to defend the Win Wa police station in Thayetchaung Township along the Dawei-Myeik Union Highway when it came under attack. Airstrikes were also conducted in areas around Thein Khun village in Tanintharyi Township, where prolonged fighting has occurred.

While the junta’s air campaign has inflicted casualties on resistance fighters, the number of civilian deaths and injuries has been significantly higher, underscoring the indiscriminate nature of these attacks.

Furthermore, the constant presence of junta aircraft conducting aerial reconnaissance throughout Tanintharyi region has instilled widespread fear and anxiety in the local population.

The human toll: Displacement and fear

The consequences of these attacks have been widespread displacement and a pervasive atmosphere of fear. The relentless air campaign has forced entire communities to abandon their homes and seek refuge in forests or displacement camps.

At least 34,300 people have been displaced across Dawei, Launglon, Yebyu and Thayetchaung townships in Dawei district.

In Myeik district, the displacements in Palaw, Tanintharyi, Myeik and Kyunsu townships reached at least 41,000 people due to fighting and naval and aerial attacks.

This mass exodus has created a humanitarian crisis, with thousands in urgent need of food, shelter and medical care.

Many villagers have fled into forests or other remote areas seeking safety. But not all are able to escape.

“Some elderly people and those with illnesses remain in the village,” said a resident of Oaktu village in Thayetchaung Township.

“Many were left behind just last week. Their children, the able-bodied youth, have fled.”

This leaves the most vulnerable – the sick, elderly and disabled – trapped in harm’s way, often without access to sufficient food or care.

The constant threat of airstrikes has also taken a severe psychological toll on civilians. Residents live in perpetual fear, with the sound of aircraft triggering anxiety and panic.

One Launglon resident described how the fear has changed the fabric of daily life: “When fighting breaks out and they [the junta] suffer losses, they retaliate with airstrikes. That’s what we’re most worried about.”

Residents also report that the attacks appear indiscriminate, even targeting areas where there are no armed groups.

“Because fighting broke out in our village the other week, I think they resent us more,” said a local resident. “They assume PDF [People’s Defense Force] members are staying in our village. But there are no PDF members here.”

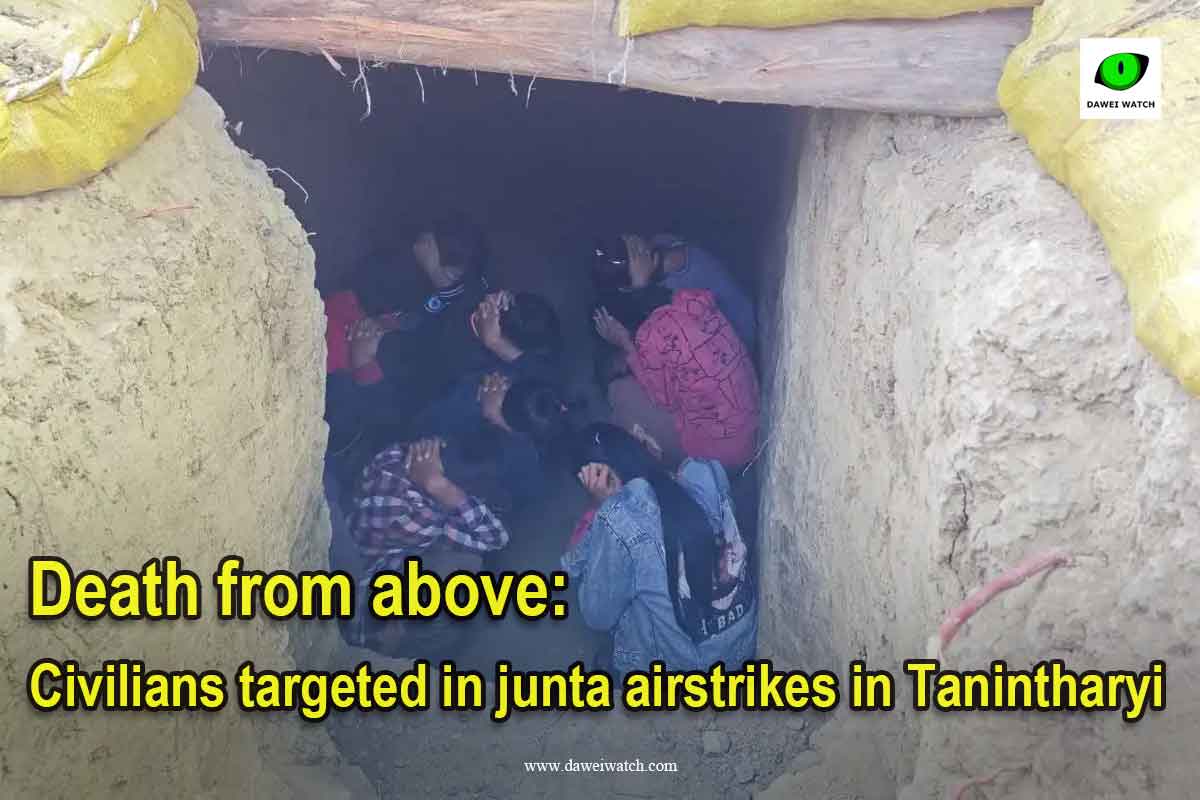

No shelter, no guidance

Adding to the civilians’ vulnerability is the lack of adequate shelter and guidance on how to protect themselves from aerial attacks. Many rely on rudimentary and potentially ineffective strategies, such as seeking refuge in forests.

“We think we’ll be safe if we’re in the forests and among the trees,” said a resident of Oaktu village, describing a survival strategy based on guesswork rather than effective protection.

Fear of junta reprisals also prevents communities from building shelters, and in densely populated homes, there is little room to hide.

“We can’t risk building bunkers – the junta would punish us if they found them,” explained the Launglon resident. “And our house has no space. When bombs fall, we just hide wherever we can: under furniture, in the toilet, anywhere.”

A growing humanitarian crisis

As the attacks continue, entire towns are emptying out. One resident described a haunting transformation in Launglon: “Come and see! Launglon is not like the Launglon of before. The people are all gone. They’ve moved away on their own. It’s deserted.”

Others speak of living with the constant noise of military aircraft – drones, helicopters, paramotors and planes – that have become part of daily life.

The testimonies from Tanintharyi reveal a humanitarian emergency unfolding under the shadow of aerial warfare. As the junta doubles down on its use of airpower, thousands of civilians face the grim reality of displacement, trauma and the daily threat of death from above.

With little international attention on the region and no formal aid reaching many affected communities, residents remain trapped between the fear of staying and the danger of fleeing.

“We hear the sound every day. When we hear it, we can’t eat. Our chests pound and we feel sick,” said one local woman.