Beneath a makeshift extension on the ground floor of a dilapidated two-story house, a newborn baby lies on his back, sleeping on a rattan bed.

Suddenly, he cries out loudly.

Daw Htwe, his adoptive mother, rushes from the back of the house and scoops him up in her arms. The baby boy immediately calms down once nestled in her embrace.

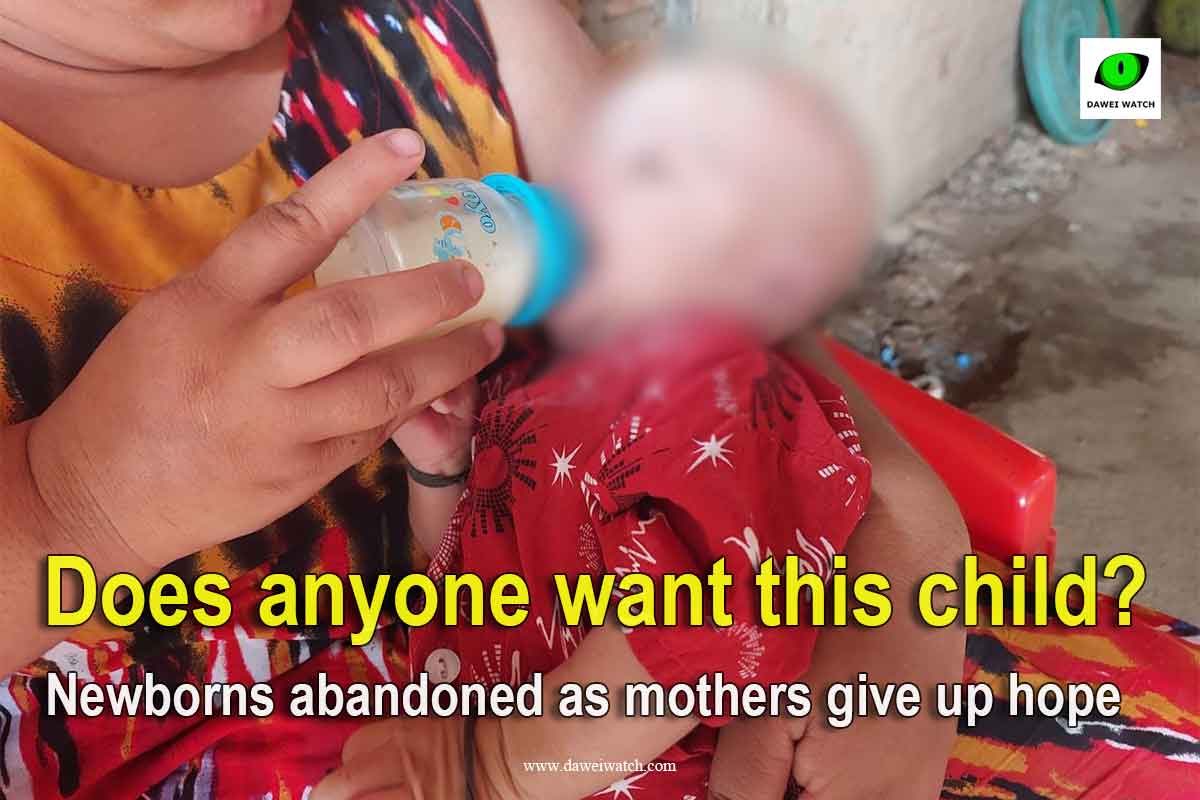

At only 39 days old, Mg Naing is an orphaned infant – abandoned, unwanted and now living with a foster mother. With his lower body bare, he lies quietly sucking instant formula from his bottle, not his birth mother’s nutritious milk.

“His mother had plenty of milk, but she never let him breastfeed. She said she didn’t want this baby and planned to throw him away nearby, so I adopted him,” Daw Htwe explained.

Daw Htwe and the baby’s paths crossed at Dawei General Hospital.

A young woman, carrying her newborn who had just left her womb, went from room to room in the hospital ward, asking in her Karen accent: “Does anyone want this child?”

People looked at the young woman with compassion, but no one offered to adopt the child. The ethnic Karen woman giving away the newborn was Ma Ni, originally from Heinda village in Dawei district.

Daw Htwe, lying on her hospital bed, witnessed the heart-wrenching scene of the young Karen woman desperately trying to give away her days-old son.

Finally, Daw Htwe decided to adopt the child.

Abandoned children

According to information obtained by Dawei Watch, at least four cases of newborns being abandoned or offered up for adoption by their birth parents happened within only 50 days in Dawei district alone.

Two of these incidents took place at private clinics, and the other two at the Dawei General Hospital, all between April and early May 2025. A similar case was also reported in 2023, when a newborn was given away at a hospital in Dawei operated by the military council.

These incidents are only those Dawei Watch has been able to document around Dawei. The actual number on the ground could be much higher. The ongoing conflict and escalating violence in the region have made communications difficult, severely limiting the availability of information.

Women’s rights groups and local charities noted that newborn abandonment had become increasingly common since the military coup. Dawei Watch’s own records also show that such cases have continued to emerge across multiple locations over the past four years.

The dire circumstances forcing mothers in Dawei to abandon their newborn babies directly contravene Myanmar’s obligations under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which guarantees every child’s right to survival, protection and development.

World ablaze as the young are sacrificed

Since the 2021 coup, families – the small worlds that make up Myanmar – have been burning in their own ways.

Insecurities amidst the conflict, fear, homes getting torched, the horrific sight of dead bodies, the struggles for livelihoods, difficulties in education and countless other hardships and sorrows make raising a child a formidable challenge.

Ma Ni was also a victim of this harsh era.

She married young and at 19, her husband abandoned her. Left pregnant, Ma Ni even tried to abort her pregnancy, but was unsuccessful.

“She couldn’t even pay her room rent. She said if she keeps this child, she wouldn’t be able to work,” Daw Htwe said as she recounted Ma Ni’s story from their time at the hospital.

Daw Htwe described Ma Ni as fair-skinned, slender and young, an inherently beautiful Karen woman. However, life has been tough for her. She had a job at the Heinda mine, but after the military coup, the mine ceased operations and she became unemployed.

In the Dawei eastern region, near Heinda village where the Heinda mine is located, the KNU’s Brigade 4 is based, along with the Kawthoolei Army (KTLA) and People’s Defense Forces (PDFs) that emerged after the coup.

The Dawei-Htee Khee road, a crucial border trade route, has become a frontline battleground as the junta’s troops and resistance forces vie for control.

Since 2023, the military has cut off phone and internet lines, as well as the transportation of food, medicine and fuel to the eastern region. The region has been so severely affected by food shortages that people ask for “rice, not money” in exchange for their labor.

Local residents have abandoned their livelihoods and are struggling to survive amidst the ongoing conflict.

In such a harsh and desperate situation, how could a jobless, income-less, single woman like Ma Ni possibly raise a helpless child?

“When she came to the hospital, her parents weren’t with her. Her husband wasn’t there either. Only one female friend accompanied her. When I asked, she said her parents had passed away. Her husband left, saying he was going to work, and never came back,” Daw Htwe recalled.

Power vacuum

Although cases of child abandonment existed even before the military coup, they appear to have increased significantly in its aftermath, according to Mae Kyin, a women’s rights activist based in Dawei.

“When people face economic hardship and pressure from all sides, it’s not easy to bear the burden of a child. In such times, they can’t think about their child’s future and end up giving them away, saying, ‘whatever happens, happens,’” Mae Kyin explained.

She added that since the coup, the absence of rule of law has also led to a rise in the sexual exploitation of women and domestic violence in the region, factors that directly contribute to child abandonment.

The four cases of child abandonment known to Dawei Watch are indeed linked to sexual exploitation, domestic violence and livelihood struggles.

The economic hardship and violence contributing to these tragic decisions underscore the broader failure to uphold the rights of women, as outlined in the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW).

Since the coup, many family members have had to go abroad for work due to worsening economic conditions. During such family separations, social complications arise, leading to incidents where children are given away to unrelated individuals.

One such incident occurred this year in Launglon Township.

In another recent case from the same township, a newborn was given away to someone, and the mother subsequently left for Thailand. In yet another instance, a woman who was abandoned by her partner during pregnancy gave her child away after giving birth.

Ma Ni’s case, however, was due to economic hardship.

Although health workers at Dawei Hospital and Daw Htwe repeatedly tried to persuade her not to abandon the baby, Ma Ni, who couldn’t even consistently pay her monthly room rent of 70,000 kyats, seemed unwilling to bring the child into her struggling life. She decided to give the baby away.

“I bought her meals and everything while she was in the hospital. I even paid her room rent. She was overjoyed when I gave her 100,000 kyats,” said Daw Htwe, holding her fair-skinned, chubby adoptive son close to her chest.

After Ma Ni handed over her baby, she quietly left Dawei Hospital and has not been in contact since.

Pawns in the ongoing conflict

Under the decay of a broken regime, heartbreaking cases of parents like Ma Ni abandoning their children are heard time and time again, yet no one takes meaningful action. It has become a normalized, almost routine occurrence.

Children abandoned by their birth parents often end up in monasteries, with religious organizations, nearby relatives or with people looking to adopt.

A former chairperson of the Tanintharyi Region Association for the Reduction of Child Abandonment observed with sorrow that as the conflict drags on, civilians are increasingly becoming casualties of war, and children are turning into collateral damage.

U Aung Myo Min, the Human Rights Minister of the National Unity Government (NUG), also stated that since the military coup, children in Myanmar have lost all fundamental rights guaranteed under the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

“All the core rights of children, the right to life, the right to development, the right to protection and the right to participation are being lost in our country,” U Aung Myo Min said in his speech on World Children’s Day.

During the NLD government’s tenure, the Association for the Prevention, Care and Protection of Abandoned Children were widely established across the country to help prevent and reduce cases of newborn abandonment.

However, after the coup, such initiatives have virtually ceased.

In the past, child welfare efforts were a collaboration between the government, community and charities. Now, the few remaining solutions rely on adoptions by unrelated individuals.

Mg Naing, the month-old baby abandoned by Ma Ni, is now peacefully sleeping in the arms of his unrelated adoptive mother, gently sucking on his bottle.

Looking down with compassion at the innocent child sleeping in her arms, Daw Htwe sighs. “This child is so unlucky to be born in a time like this.”